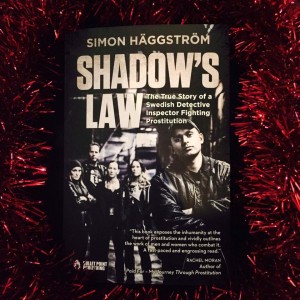

If I could make every adult inhabitant of the planet read one book in 2017, it would be Shadows Law [translated by Selina Öberg and published by Bullet Point Publishing, from the original Swedish Skuggans lag, published by Kalla Kulor Förlag] written by Stockholm policeman Simon Häggström. In just four hundred pages he makes us see a hidden world, one that it would be too easy and self-consoling to call obscene. In the narratives of his experiences of long squalid nights in a car trying to arrest clients of prostitutes, Häggström is able to tell the story of millions of women, of thousands of years of history, of billions of violations. A difficult book, obviously, but imperative, necessary, revelatory.

If I could make every adult inhabitant of the planet read one book in 2017, it would be Shadows Law [translated by Selina Öberg and published by Bullet Point Publishing, from the original Swedish Skuggans lag, published by Kalla Kulor Förlag] written by Stockholm policeman Simon Häggström. In just four hundred pages he makes us see a hidden world, one that it would be too easy and self-consoling to call obscene. In the narratives of his experiences of long squalid nights in a car trying to arrest clients of prostitutes, Häggström is able to tell the story of millions of women, of thousands of years of history, of billions of violations. A difficult book, obviously, but imperative, necessary, revelatory.

To describe this treatise I need to make a long introduction, which I hope will be interesting. Since as long ago as 1999, prostitution in Sweden has been a crime for those who exploit it and for those who pay for its services, but not for the person whose body is being bought (whether she is selling it herself or, as happens much more often, through someone who is exploiting her), for the prostitute is considered a victim of sexual abuse even if she appears to be “consenting”. In fact, the women involved in this practice are considered either victims of force or psychological victims. In the former cases, this occurs through a system of slavery and blackmail (either physical or moral) by a pimp; or out of financial need, as often happens, for example, with foreign women that in their country of origin would live under the poverty threshold. With the psychological victims (who are often the same ones who end up caught in the grip of blackmail), they are almost always women who have experienced sexual abuse during childhood or early adolescence, especially if the abuse took place within the family. When a child experiences sexual abuse (whether it is carried out in a violent act or – as is more often the case – as psychological manipulation), it often indelibly shatters the sanctity of their bodies, obliterating their sense of worth and, above all, their integrity. An abused young girl loses her corporeal boundaries and the filth that has touched her remains inside like a sin that she didn’t have the means to return to the sender. In the most serious and fragile cases, with difficulty a woman finds within herself the means to cicatrize this type of experience and thus often the result is that she will set into motion a mechanism of paradoxical self-defense and self-damage: exposing herself, offering herself sexually, to the point of putting her own body up for sale. Behind every flirtatious and “voluptuous” woman, even to the point of prostituting herself, there is often an abused and very wounded woman, who behaves this way to obtain two emotional results. The first is the aleatory illusion of having control over men, a power ransom (“you are buying me because in order to have me you’re willing to pay even” = “I have power over you” = “I can manipulate you, in contrast to that monstrous feeling of abuse, impotence and submission that I experienced as a child”). The second, even more horrendous, is that the abused girls (and children in general who are mistreated) tend to blame themselves for what happened, in the irrevocable, fetid conviction that they deserved it. So, in this sense, prostitution becomes a way of continuing to punish themselves, in a perverse spiral of debasement and atonement.

These are the foundations that anyone who deals with prostitution from a psychological and/or social point of view knows very well, and this is the world that Simon Häggström describes, with a cinematographic, moving, painful, exhausting touch. Little David Simon, who every day meets a Goliath – unfortunately not a single huge giant to conquer once and for all, but a fragmented, particulate essence of Evil that seems impossible to tackle. The rotten men he battles with: the exploiters of prostitution and the users, their inexorable greed, their evil need to dominate, possess, abuse. Because no one can truly be that ingenuous as to not know that a woman who sells sex doesn’t do it for pleasure, and when she pretends to, it is so the client will finish quickly, and/or to avoid him hurting her – him or whoever is selling her. A prostitute, no matter how tough her stance, is one of the most fragile adult beings in the world, and this assumption – which imbibes the entire book with an immense pietas –nurtures the sense of wounded femininity that every woman knows because she carries it inside herself. To read Häggström is a reparation, an opened up possibility. Any man who hates women so much that he will buy them is defeated by this policeman with the tattered heart who tries to put a space between his life and this horror, but often doesn’t succeed, and all the impotence of feeling like a drop in the ocean has turned him into a wise man telling the story, not of a profession, but of a mission.

The stories that Häggström has chosen to tell are typological examples of what he encounters, and at the end of reading it, every one of our veils, questions or doubts have received an answer. This clarity, this almost taxonomic narration, offers us a powerful picture that in some ways gives us the consolation of feeling that there are knowable and thus maybe controllable dynamics. That if David were not left on his own, and instead there were many Davids for every lost fragment of Goliath, there would be a chance of putting an end to this slavery and self-injury, to this cannibalism of youth and beauty that has nothing to do with sexual pleasure but is only about subjugation and enjoying that subjugation, just like in a rape.

And beyond the respect and love for women that this book contains, it is an engrossing tale written with a wonderful pen in which every word is important, elegant and meaningful. Häggström’s talent undoubtedly stems from an expressive and cathartic need, but his is a true Writing, and it would be great if one day he could continue to be a writer without it being a way to filter this pain.

In the meantime, we women, all together, owe him a huge thank you.

Originally written in Italian for La poesia e lo spirito. Translated by Ellen McRae